Neurokognition II

SS2014

Inhalte

Die Veranstaltung führt in die Modellierung neurokognitiver Vorgänge des Gehirns ein. Neurokognition ist ein Forschungsfeld, welches an der Schnittstelle zwischen Psychologie, Neurowissenschaft, Informatik und Physik angesiedelt ist. Es dient zum Verständnis des Gehirns auf der einen Seite und der Entwicklung intelligenter adaptiver Systeme auf der anderen Seite. Die Neurokognition II beleuchtet komplexere Modelle von Neuro-psychologischen Prozessen, mit dem Ziel neue Algorithmen für intelligente, kognitive Roboter zu entwickeln. Themen sind Wahrnehmung, Gedächtnis, Handlungskontrolle, Emotionen, Entscheidungen und Raumwahrnehmung. Zum tieferen Verständnis erfordern die Übungen auch praktische Aufgaben am Rechner.

Randbedingungen

Empfohlene Voraussetzungen: Grundkenntnisse Mathematik I bis IV, Neurokognition I

Prüfung: Mündliche Prüfung

Ziele: Fachspezifische Kenntnisse der Neurokognition

Syllabus

Introduction

The introduction motivates the goals of the course and basic concepts of models. It further explains why computational models are useful to understand the brain and why cognitive computational models can lead to a new approach in modeling truly intelligent agents.

The styles of computation used by biological systems are fundamentally different from those used by conventional computers: biological neural networks process information using energy-efficient asynchronous, event-driven, methods. They learn from their interactions with the environment, and can flexibly produce complex behaviors. These biological abilities yield a potentially attractive alternative to conventional computing strategies.

Neurokognition II is particularly devoted to model perception cognition and behavior in large-scale neural networks. The course introduces models of early vision, attention, object recognition, space perception, cognitive control, memory, emotion and consciousness.

Part I Anatomy

1.1 Anatomy

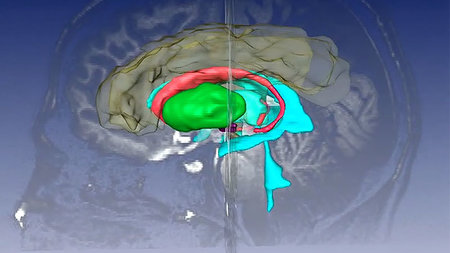

This lecture gives a brief introduction into brain anatomy and provides information about the function of multiple brain areas and nuclei.

Exercise I.1: Anatomy.

Part II Early Vision

Perhaps our most important sensory information about our environment is vision. The lecture "early vision" explains the first processing steps of visual perception.

Overview:Adelson, E. H., Bergen, J R. (1985): Spatiotemporal energy models for the perception of motion. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. 2:284-299

DeAngelis, G., Ohzawa, I., Freeman, R.D. (1995): Receptive-field dynamics in the central visual pathways. TINS Vol. 18, No. 10, 1995

Vision starts in the retina, which is considered part of the brain. The lecture explains the concept of a receptive field and introduces simple models of early processing that model dynamic receptive fields.

Additional Reading:Cai D, DeAngelis GC, and Freeman RD (1997) Spatiotemporal receptive field organization in the LGN of cats and kittens. J Neurophysiol 78:1045-1061.

Shape perception refers to the fact that the visual system has filters that respond optimally to oriented bars or edges, which takes place in area V1, also called striate cortex. This lecture introduces into the receptive fields of neurons in V1 and explains what kind of information V1 encodes with respect to shape perception.

Exercise II.1: Gabor filters, Files: exercise2.tar.gz

Color perception starts in the retina, since we have receptors that are selective for different wavelength of the light. This lecture introduces into models of color selective receptive fields.

In the cortex, the visual space is overrepresented in the fovea, which means that much more space in cortex is devoted to compute information around the center of visual space. A cortical magnification function allows to model the relation between visual and cortical space providing a method to account for the overrepresentation in models of visual perception.

Suggested Reading: Rovamo J, Virsu V (1983) Isotropy of cortical magnification and topography of striate cortex. Vision Res 24: 283-286.

Motion perception begins already in area V1 by motion sensitive cells and then continues in the dorsal pathway in areas MT and MST.

Suggested Reading:Adelson, E. H., Bergen, J R. (1985): Spatiotemporal energy models for the perception of motion.

Seeing in three dimensions requires to extract depth information from the visual scene. One method, called binocular disparitiy, is of primary focus.

Suggested Reading: Read JCA (2005) Early computational processing in binocular vision and depth perception. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 87:77-108.

Exercise II.2: Depth perception, Files: exercise3.tar.bz2

Gain normalization appears to be a canonical neural computation in sensory systems and possibly also in other neural systems. Gain normalization is introduced and examples for normalization in retina, in primary visual cortex, in higher visual cortical areas and in non-visual cortical areas are given.

Suggested Reading: Carandini M., Heeger DJ. (2012) Normalization as a canonical neural computation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13:51-62.

Why does the brain develop a particular set of feature detectors for early vision. This lecture addresses how approaches that rely on learning allow to better understand the coding of vision in the brain.

Suggested Reading:

Wiltschut, J., Hamker, F.H. (2009) Efficient Coding correlates with spatial frequency tuning in a model of V1 receptive field

organization. Visual Neuroscience. 26:21-34

Teichmann, M., Wiltschut, J., Hamker, F.H. (2012) Learning invariance from natural images inspired by observations in the primary visual cortex. Neural Computation, 24: 1271-1296

Additional Reading:

Simoncelli, E.P., Olshausen, B. A.: Natural Image

Statistics and Neural Representation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001. 24:1193-216

Simoncelli, E.P.: Vision and the statistics of the visual environment. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2003, 13:144-149._

Exercise II.3: Efficient coding, Files: exercise4.tar.bz2

Part III High-level Vision

High-level vision deals with questions of how we recognize objects or scenes and how we direct processing resources to particular aspects of visual scenes (visual attention).

3.1 Object recognitionObject recognition appears to be solved by a hierarchically organized system that progressively increases the complexity and invariance of feature detectors.

Suggested Reading:

Riesenhuber, M, Poggio, T (1999) Hierarchical models of object recognition in cortex, Nat. Neurosci. 2:1019-1025.

Serre, T, Wolf, L, Bileschi, S, Riesenhuber, M, Poggio, T (2007) Object recognition withcortex-like mechanisms. In: IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and MachineIntelligence, 29:411-426.

Exercise III.1: Object Recognition and HMAX, Files: exercise5.tar.bz2 ; article: Serre, Wolf and Poggio (2004).

Attention refers to mechanisms that allow the focusing of processing resources. Experimental observations, neural principles and system-level models of attention are described.

Suggested Reading:

Hamker, F. H. (2005) The emergence of attention by population-based

inference and its role in distributed processing and cognitive control of

vision. Journal for Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 100:64-106.

Reynolds JH, Heeger DJ (2009) The normalization model of attention. Neuron 61: 168-185.

Exercise III.2: Normalization model of attention, Files: exercise6.tar.bz2 .

Exercise III.3: Visual attention and experimental data, Files: exercise7.tar.bz2 .

The perception of space is very crucial for systems that interact with the world. This lecture introduces to anatomical pathways of space perception. The primary focus is then directed to the problem of "Visual Stability", which deals with the question of why we perceive a stable environment regardless that each eye movement changes the content on the retina.

Suggested Reading:

Ziesche, A., Hamker, F.H. (2014)

Brain circuits underlying visual stability across eye movements - converging evidence

for a neuro-computational model of area LIP.

Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, 8(25), 1-15

Hamker, F. H., Zirnsak, M., Ziesche, A., Lappe, M. (2011) Computational

models of spatial updating in peri-saccadic perception. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2011), 366:

554-571.

Husain, M., Nachev, P. (2006) Space and the parietal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences,

11:30-36.

Part IV Cognition

Cognition deals with questions of how a system can learn and execute complex tasks and allow control over sensors and actions.

Suggested Reading:

Bird, C.M., Burgess, N. (2008) The hippocampus and memory: insights from spatial processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9:182-194.

4.2 Motor decision and Parkinson disease

Suggested Reading:

Vitay, J., Fix, J., Beuth, F., Schroll, H., Hamker, F.H. (2009) Biological

Models of Reinforcement Learning. Künstliche Intelligenz, 3:12-18.

Wiecki, T.V., Frank, M.J. (2010) Neurocomputational models of motor and

cognitive deficits in Parkinson's disease. Prog. Brain Res. 183:275-297.

4.4 Cognition. Episodic Memory and Goals

Exercise IV.1: ANNarchy simulator, File: exercise08.tar.gz, slides

Exercise IV.2: Basal ganglia, Files: exercise9.tar.gz

Exercise IV.3: Space perception, Files: exercise10.zip